Nonlinear Optimal Control

Optimal control aims at finding a control function that minimises (or maximises) a given criterion subject to system dynamics, typically governed by differential equations, and path constraints. A generic continuous-time Optimal Control Problem (OCP) is often written in the following form:

where \(\tau \in \mathbb{R}\) denotes time, \(x(\tau) \in \mathbb{R}^{n_x}\) is the state of the system, \(u(\tau) \in \mathbb{R}^{n_u}\) is the vector of control inputs and \(p \in \mathbb{R}^{n_p}\) is the vector of parameters. The function \(\mathit{\Phi} : \mathbb{R}^{n_x} \times \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}^{n_p} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is the terminal cost function and \(\mathit{L} : \mathbb{R}^{n_x} \times \mathbb{R}^{n_u} \times \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}^{n_p} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is called the running cost. The system dynamics are given by the function \(f : \mathbb{R}^{n_x} \times \mathbb{R}^{n_u} \times \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}^{n_p} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{n_x}\), \(g : \mathbb{R}^{n_x} \times \mathbb{R}^{n_u} \times \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}^{n_p} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{n_g}\) is the path constraint function, and finally \(\psi : \mathbb{R}^{n_x} \times \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}^{n_p} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{n_{\phi}}\) is the terminal constraint function.

Numerical Methods

PolyMPC is designed to solve OCPs of the form described above. Unlike other software tools for real-time optimal control, PolyMPC features optimised embeddable implementation of Chebyshev Pseudospectral Method. Pseudospectral collocation is a numerical technique that employs a polynomial approximation of the state and control trajectories to discretize continuous-time OCPs. Initially developed for solving differential equations, the collocation method was adopted for optimal control problems by Biegler [Biegler1984] and further analysed and developed by Ross [Fahroo2003], Benson [Benson2005] and Huntington [Huntington2007] in the early 2000s. One distinctive feature of this method is that the solution of a system of differential equations and optimisation of the cost function happen simultaneously. It also inherits the stability properties of the collocation method for ODEs, and therefore is particularly useful for stiff nonlinear and unstable systems. Furthermore, for some smooth problems the method can exhibit very fast, or spectral, convergence.

Chebyshev Pseudospectral Method

Assuming the approximate solution for the state and control trajectories are represented by an appropriately chosen set of basis functions \(\phi_{k}(\cdot)\):

the collocation approach requires that the differential equation is satisfied exactly at a set of collocation points \(t_j \in (t_0, \ t_f)\):

With some initial conditions: \(x^{N}(t_0) = x_0\). Formulas represent a function expansion in the nodal basis, where \(x_k\) is the value of \(x(t)\) at the node \(t_k\) and \(\phi_{k}\) denotes a specific cardinal basis function, which satisfies the condition: \(\phi_{j}(t_i) = \delta_{ij}, \ i,j = 0,...,N\), where:

A common choice of the cardinal basis in pseudospectral methods is the characteristic Lagrange polynomial of order \(N\). This means that each basis function reproduces one function value at a particular point in the domain. The general expression for these polynomials is given by:

Using the approximations above one can compute derivatives of the state trajectory at the nodal points:

where \(D_{jk}\) are elements of the interpolation derivative matrix \(\mathbf{D}\). And the approximate solution to the differential equation satisfies a system of algebraic equations:

A careful choice of collocation points is crucial for numerical accuracy and convergence of the collocation method. An equidistant spacing of the collocation nodes is known to cause an exponential error growth of the polynomial interpolation near the edges of the domain, an effect called Runge’s phenomenon.

In the PolyMPC we employ the most commonly used set of \(N+1\) Chebyshev Gauss-Lobatto (CGL) points:

Using Chebyshev polynomials in the collocation scheme is not efficient because they do not satisfy the cardinality condition, and therefore we will be using CGL nodes, which allow us to avoid Runge’s phenomenon, in combination with Lagrange polynomials to solve the system differential equations.

Cost Function

The Mayer term of the cost function can be trivially approximated at the last collocation point:

For the Lagrange term approximation using the CGL set of points it is convenient to utilize the Clenshaw-Curtis quadrature integration scheme, as suggested in [Trefethen2000]. The method allows one to find a set of weights \(\{\omega_j\} \in \mathbb{R}, \ j = 0, \cdots , N\) such that the following approximation is exact for all polynomials \(p(t)\) of order less than \(N\) and corresponding weight function \(\omega(t)\):

Where \(\mathbb{P}_{N}\) is the space of polynomials of degree less or equal than \(N\) and \(p(t)\) is a Chebyshev approximation of the integrated function:

Note

The pseudospectral collocation method helps to transform the continous optimal control into a finite dimensional nonlinear optimisation problem (Nonlinear Programming) with respect to polynomial expansion coefficients. More details on the implementation of the numerical method and extension to spline can [Listov2020].

Modelling Optimal Control Problems

Following the PolyMPC concept, the user should specify the problem dimensions and data types at compile-time. This is done to enable embedded applications of the tool.

Problem: The user specifies an OCP by deriving from theContinuousOCPclass. At this point the problem contains meta data such as dimensions, number of constraints, state and control data types, functions to evaluate cost and constraints. The derivedProblemclass becomes a nonlinear problem and can passed to an NLP solver.Approximation: This defines the control and state approximating function and numerical scheme. This is typically aSplineclass orPolynomial.Sparsity [Optional (SPARSE/DENSE), Default: DENSE]: This template argument defines whether sparse or dense representation of problem sensitivities should be used.

A Guiding Example

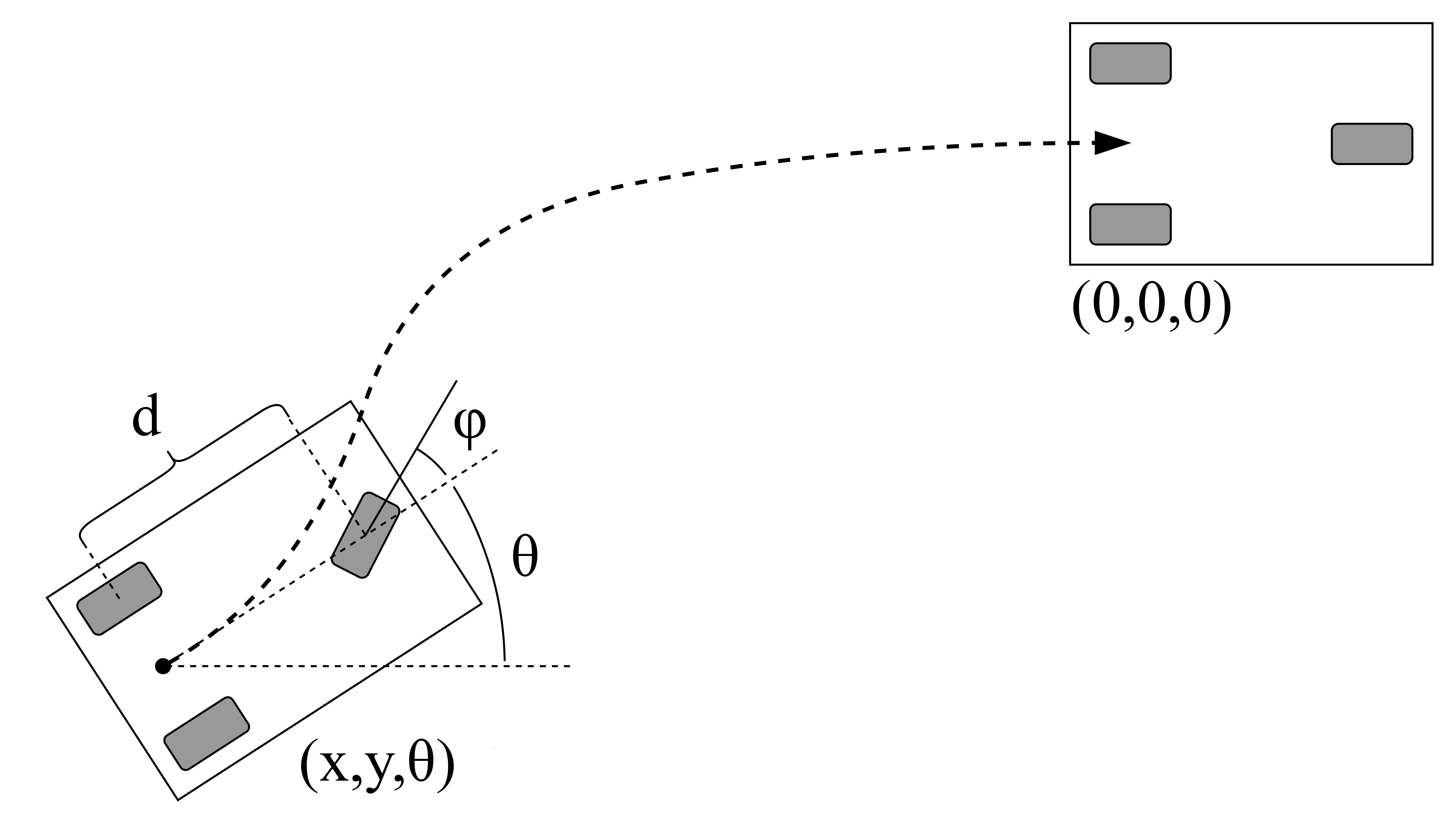

Let us demonstrate the functionality of software on a simple automatic parking problem. We will consider a simple mobile robot that should park at a specific point with a specified orientation \([0,0,0]\) starting from some point \((x,y,\theta)\), which is illustrated in the figure below.

The robot is controlled by setting front wheel velocity \(v\) and the steering angle \(\phi\), \(d\) denotes the wheel base of the robot. Assuming no wheel slip and omitting dynamics, the robot differential equation can be written as:

One option to drive the robot to a desired spot is to penalise the squared distance to the target in the cost function. Below, we show how to formulate and solve such problem using PolyMPC.

#include "polynomials/ebyshev.hpp"

#include "polynomials/splines.hpp"

#include "control/continuous_ocp.hpp"

#include "utils/helpers.hpp"

#include <iomanip>

#include <iostream>

#include <chrono>

#define POLY_ORDER 5

#define NUM_SEG 2

/** benchmark the new collocation class */

using Polynomial = polympc::Chebyshev<POLY_ORDER, polympc::GAUSS_LOBATTO, double>;

using Approximation = polympc::Spline<Polynomial, NUM_SEG>;

POLYMPC_FORWARD_DECLARATION(/*Name*/ RobotOCP, /*NX*/ 3, /*NU*/ 2, /*NP*/ 0, /*ND*/ 1, /*NG*/0, /*TYPE*/ double)

using namespace Eigen;

class RobotOCP : public ContinuousOCP<RobotOCP, Approximation, SPARSE>

{

public:

~RobotOCP() = default;

RobotOCP()

{

/** initialise weight matrices to identity (for example)*/

Q.setIdentity();

R.setIdentity();

QN.setIdentity();

}

Matrix<scalar_t, 3, 3> Q;

Matrix<scalar_t, 2, 2> R;

Matrix<scalar_t, 3, 3> QN;

template<typename T>

inline void dynamics_impl(const Ref<const state_t<T>> x, const Ref<const control_t<T>> u,

const Ref<const parameter_t<T>> p, const Ref<const static_parameter_t> &d,

const T &t, Ref<state_t<T>> xdot) const noexcept

{

polympc::ignore_unused_var(p);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(t);

xdot(0) = u(0) * cos(x(2)) * cos(u(1));

xdot(1) = u(0) * sin(x(2)) * cos(u(1));

xdot(2) = u(0) * sin(u(1)) / d(0);

}

template<typename T>

inline void lagrange_term_impl(const Ref<const state_t<T>> x, const Ref<const control_t<T>> u,

const Ref<const parameter_t<T>> p, const Ref<const static_parameter_t> d,

const scalar_t &t, T &lagrange) noexcept

{

polympc::ignore_unused_var(p);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(t);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(d);

lagrange = x.dot(Q * x) + u.dot(R * u);

}

template<typename T>

inline void mayer_term_impl(const Ref<const state_t<T>> x, const Ref<const control_t<T>> u,

const Ref<const parameter_t<T>> p, const Ref<const static_parameter_t> d,

const scalar_t &t, T &mayer) noexcept

{

polympc::ignore_unused_var(p);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(t);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(d);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(u);

mayer = x.dot(QN * x);

}

};

Below we will look into the code in more detail.

#include "polynomials/ebyshev.hpp"

#include "polynomials/splines.hpp"

#include "control/continuous_ocp.hpp"

#include "utils/helpers.hpp"

These headers contain classes necessary to define the approximation (Chebyshev polynomials, splines) and ContinuousOCP. The header utils/helpers.hpp constains

some useful utilities.

#define POLY_ORDER 5

#define NUM_SEG 2

using Polynomial = polympc::Chebyshev<POLY_ORDER, polympc::GAUSS_LOBATTO, double>;

using Approximation = polympc::Spline<Polynomial, NUM_SEG>;

POLYMPC_FORWARD_DECLARATION(/*Name*/ RobotOCP, /*NX*/ 3, /*NU*/ 2, /*NP*/ 0, /*ND*/ 1, /*NG*/0, /*TYPE*/ double)

Here, we choose the parameters of the approximation: two-segement spline with Lagrange polynomials of order 5 in each segment. Furthermore, polympc::GAUSS_LOBATTO

with Chebyshev class means that we will be using Chebyshev-Gauss-Lobatto collocation scheme. Next, similar to nonlinear programs, macro POLYMPC_FORWARD_DECLARATION

creates class traits for the class RobotOCP to infer compile time information. Here, NX is again the dimension of the state space, NU- control, NP- variable

parameters, ND- static parameters, NG- number of constraints, and finally the scalar type (double in this case).

Note

The NP parameters, unlike static ND parameters can be changed by the nonlinear solver during iterations. ND parameters can be changed by the user inbetween solver

calls. ND parameters are reduntant, strictly speaking, as mutable attributes of RobotOCP can be used instead; this feature is primarily exists for compatibility of

Eigen and CasADi interfaces.

Let’s now move on to defining the dynamics functions.

class RobotOCP : public ContinuousOCP<RobotOCP, Approximation, SPARSE>

{

public:

~RobotOCP() = default;

RobotOCP()

{

/** initialise weight matrices to identity (for example)*/

Q.setIdentity();

R.setIdentity();

QN.setIdentity();

}

Matrix<scalar_t, 3, 3> Q;

Matrix<scalar_t, 2, 2> R;

Matrix<scalar_t, 3, 3> QN;

template<typename T>

inline void dynamics_impl(const Ref<const state_t<T>> x, const Ref<const control_t<T>> u,

const Ref<const parameter_t<T>> p, const Ref<const static_parameter_t> &d,

const T &t, Ref<state_t<T>> xdot) const noexcept

{

polympc::ignore_unused_var(p);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(t);

xdot(0) = u(0) * cos(x(2)) * cos(u(1));

xdot(1) = u(0) * sin(x(2)) * cos(u(1));

xdot(2) = u(0) * sin(u(1)) / d(0);

}

Here, ContinuousOCP creates templated types for state (state_t), control (control_t), parameters (parameter_t), derivatives (state_t).

Static parameter type is not templated. Templates are necesary to propagate special AutoDiffScalar type objects through the user-defined functions in order to compute

sensitivities. The user should implement dynamics_impl() function with a given particular signature. Function ignore_unused_var() is here merely to suppress compiler

warnings about unused variables, it does not add any computational overhead.

As a next step we will define a cost that penalises the squared distance of the robot from the target, which may look like one below:

In the code, the user has to implement Lagrange (lagrange_term_impl()) and Mayer (mayer_term_impl()) terms. By default, \(t_0= 0.0\) and \(t_f = 1.0\), we

will explain in the next section how to chenge these values.

template<typename T>

inline void lagrange_term_impl(const Ref<const state_t<T>> x, const Ref<const control_t<T>> u,

const Ref<const parameter_t<T>> p, const Ref<const static_parameter_t> d,

const scalar_t &t, T &lagrange) noexcept

{

polympc::ignore_unused_var(p);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(t);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(d);

lagrange = x.dot(Q * x) + u.dot(R * u);

}

template<typename T>

inline void mayer_term_impl(const Ref<const state_t<T>> x, const Ref<const control_t<T>> u,

const Ref<const parameter_t<T>> p, const Ref<const static_parameter_t> d,

const scalar_t &t, T &mayer) noexcept

{

polympc::ignore_unused_var(p);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(t);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(d);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(u);

mayer = x.dot(QN * x);

}

Generic Inequality Constraints

Additionally, we could limit angular acceleration of the robot a bit. This heuristicaly can be achieved by introducing a nonlinear inequality constraint:

The user can implement this inequality constraint function in RobotOCP as shown below:

template<typename T>

inline void inequality_constraints_impl(const Ref<const state_t<T>> x, const Ref<const control_t<T>> u,

const Ref<const parameter_t<T>> p, const Ref<const static_parameter_t> d,

const scalar_t &t, Eigen::Ref<constraint_t<T>> g) const noexcept

{

g(0) = u(0) * u(0) * cos(u(1));

polympc::ignore_unused_var(x);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(d);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(t);

polympc::ignore_unused_var(p);

}

Values \(g_l\) and \(g_u\) will be set after in the solver.

Solving OCP

Now RobotOCP is in principle equivalent to a nonlinear program, i.e. the user can access cost, constraints, Lagrangian, their derivatives etc. We can proceed solving

this problem as described in Nonlinear Programming chapter. We create a nonlinear solver, set up settings.

using box_admm_solver = boxADMM<RobotOCP::VAR_SIZE, RobotOCP::NUM_EQ, RobotOCP::scalar_t,

RobotOCP::MATRIXFMT, linear_solver_traits<RobotOCP::MATRIXFMT>::default_solver>;

using preconditioner_t = RuizEquilibration<RobotOCP::scalar_t, RobotOCP::VAR_SIZE,

RobotOCP::NUM_EQ, RobotOCP::MATRIXFMT>;

int main(void)

{

Solver<RobotOCP, box_admm_solver, preconditioner_t> solver;

/** change the final time */

solver.get_problem().set_time_limits(0, 2);

/** set optimiser properties */

solver.settings().max_iter = 10;

solver.settings().line_search_max_iter = 10;

solver.qp_settings().max_iter = 1000;

/** set the parameter 'd' */

solver.parameters()(0) = 2.0;

/** initial conditions and constraints on the control signal */

Eigen::Matrix<RobotOCP::scalar_t, 3, 1> init_cond; init_cond << 0.5, 0.5, 0.5;

Eigen::Matrix<RobotOCP::scalar_t, 2, 1> ub; ub << 1.5, 0.75;

Eigen::Matrix<RobotOCP::scalar_t, 2, 1> lb; lb << -1.5, -0.75;

/** setting up bounds and initial conditions: magic for now */

solver.upper_bound_x().tail(22) = ub.replicate(11, 1);

solver.lower_bound_x().tail(22) = lb.replicate(11, 1);

solver.upper_bound_x().segment(30, 3) = init_cond;

solver.lower_bound_x().segment(30, 3) = init_cond;

/** solve the NLP */

polympc::time_point start = polympc::get_time();

solver.solve();

polympc::time_point stop = polympc::get_time();

auto duration = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::microseconds>(stop - start);

/** retrieve solution and some statistics */

std::cout << "Solve status: " << solver.info().status.value << "\n";

std::cout << "Num iterations: " << solver.info().iter << "\n";

std::cout << "Primal residual: " << solver.primal_norm() << " | dual residual: " << solver.dual_norm()

<< " | constraints violation: " << solver.constr_violation() << " | cost: " << solver.cost() <<"\n";

std::cout << "Num of QP iter: " << solver.info().qp_solver_iter << "\n";

std::cout << "Solve time: " << std::setprecision(9) << static_cast<double>(duration.count()) << "[mc] \n";

std::cout << "Size of the solver: " << sizeof (solver) << "\n";

std::cout << "Solution: " << solver.primal_solution().transpose() << "\n";

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

MPC Wrapper

Even though we can solve the OCP now, the user or control engineer is required to understand how the collocation method works and how control and state polynomial coefficients

are stored in memory which is not user friendly to say the least. Therefore, PolyMPC includes the MPC wrapper class that abstracts the numerical scheme from the user.

Additionally, since the control and state trajectories are represented by splines it is convenient to evaluate the solution at any point, or interpolate them.

Here is how our particular example will look like with the MPC wrapper:

int main(void)

{

/** create an MPC algorithm and set the prediction horison */

using mpc_t = MPC<RobotOCP, Solver, box_admm_solver>;

mpc_t mpc;

mpc.settings().max_iter = 20;

mpc.settings().line_search_max_iter = 10;

mpc.set_time_limits(0, 2);

/** problem data */

mpc_t::static_param p; p << 2.0; // robot wheel base

mpc_t::state_t x0; x0 << 0.5, 0.5, 0.5; // initial condition

mpc_t::control_t lbu; lbu << -1.5, -0.75; // lower bound on control

mpc_t::control_t ubu; ubu << 1.5, 0.75; // upper bound on control

mpc.set_static_parameters(p);

mpc.control_bounds(lbu, ubu);

mpc.initial_conditions(x0);

/** solve */

polympc::time_point start = polympc::get_time();

mpc.solve();

polympc::time_point stop = polympc::get_time();

auto duration = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::microseconds>(stop - start);

/** retrieve solution and statistics */

std::cout << "MPC status: " << mpc.info().status.value << "\n";

std::cout << "Num iterations: " << mpc.info().iter << "\n";

std::cout << "Solve time: " << std::setprecision(9) << static_cast<double>(duration.count()) << "[mc] \n";

std::cout << "Solution X: " << mpc.solution_x().transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << "Solution U: " << mpc.solution_u().transpose() << "\n";

/** sample x solution at collocation points [0, 5, 10] */

std::cout << "x[0]: " << mpc.solution_x_at(0).transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << "x[5]: " << mpc.solution_x_at(5).transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << "x[10]: " << mpc.solution_x_at(10).transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << " ------------------------------------------------ \n";

/** sample control at collocation points */

std::cout << "u[0]: " << mpc.solution_u_at(0).transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << "u[1]: " << mpc.solution_u_at(1).transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << " ------------------------------------------------ \n";

/** sample state at time 't = [0.0, 0.5]' */

std::cout << "x(0.0): " << mpc.solution_x_at(0.0).transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << "x(0.5): " << mpc.solution_x_at(0.5).transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << " ------------------------------------------------ \n";

/** sample control at time 't = [0.0, 0.5]' */

std::cout << "u(0.0): " << mpc.solution_u_at(0.0).transpose() << "\n";

std::cout << "u(0.5): " << mpc.solution_u_at(0.5).transpose() << "\n";

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

Below is the list of all currently available interface functions:

Set Time Limits

- inline void set_time_limits(const scalar_t& t0, const scalar_t& tf) noexcept

Set Initial Conditions

- inline void initial_conditions(const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& x0) noexcept

- inline void initial_conditions(const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& x0_lb, const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& x0_ub) noexcept

Set State (Trajectory) Bounds

- void x_lower_bound(const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& xlb)

- void x_upper_bound(const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& xub)

- void state_bounds(const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& xlb, const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& xub)

- void state_trajectory_bounds(const Eigen::Ref<const traj_state_t>& xlb, const Eigen::Ref<const traj_state_t>& xub)

- void x_final_lower_bound(const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& xlb)

- void x_final_upper_bound(const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& xub)

- void final_state_bounds(const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& xlb, const Eigen::Ref<const state_t>& xub)

Set Control (Trajectory) Bounds

- void u_lower_bound(const Eigen::Ref<const control_t>& lb)

- void u_upper_bound(const Eigen::Ref<const control_t>& ub)

- void control_trajecotry_bounds(const Eigen::Ref<const traj_control_t>& lb, const Eigen::Ref<const traj_control_t>& ub)

- void control_bounds(const Eigen::Ref<const control_t>& lb, const Eigen::Ref<const control_t>& ub)

Set Generic Inequalities Bounds

- void constraints_trajectory_bounds(const Eigen::Ref<const constraints_t>& lbg, const Eigen::Ref<const constraints_t>& ubg)

- void constraints_bounds(const Eigen::Ref<const constraint_t>& lbg, const Eigen::Ref<const constraint_t>& ubg)

Set Variable Parameters Bounds

- void parameters_bounds(const Eigen::Ref<const parameter_t>& lbp, const Eigen::Ref<const parameter_t>& ubp)

Set Static Parameters

- void set_static_parameters(const Eigen::Ref<const static_param>& param)

Set State Trajectory Guess (for optimiser)

- void x_guess(const Eigen::Ref<const traj_state_t>& x_guess)

Set Control Trajectory Guess (for optimiser)

- void u_guess(const Eigen::Ref<const traj_control_t>& u_guess)

Set Parameters Guess

- void p_guess(const Eigen::Ref<const parameter_t>& p_guess)

Set Dual Variable Guess (if available)

- void lam_guess(const Eigen::Ref<const dual_var_t>& lam_guess)

Set/Get NLP Solver Settings

- const typename nlp_solver_t::nlp_settings_t& settings() const

- typename nlp_solver_t::nlp_settings_t& settings()

Set/Get QP Solver Settings

- const typename nlp_solver_t::nlp_settings_t& settings() const

- typename nlp_solver_t::nlp_settings_t& settings()

Access NLP Solver Info

- const typename nlp_solver_t::nlp_info_t& info() const

- typename nlp_solver_t::nlp_info_t& info()

Access NLP Solver (object)

- const nlp_solver_t& solver() const

- nlp_solver_t& solver()

Access OCP class (object)

- const OCP& ocp() const

- OCP& ocp() noexcept

Access NLP Solver Convergence Properties

Get State Trajectory as Column or [NX x NUM_NODES] matrix

- traj_state_t solution_x() const

- Eigen::Matrix<scalar_t, nx, num_nodes> solution_x_reshaped() const

Get State Trajectory at K-th Collocation Point

- state_t solution_x_at(const int &k) const

Get State Trajectory at Time Point ‘t’ (interpolated)

- state_t solution_x_at(const scalar_t& t) const

Get Control Trajectory as Column or [NU x NUM_NODES] matrix

- traj_control_t solution_u() const

- Eigen::Matrix<scalar_t, nu, num_nodes> solution_u_reshaped() const

Get Control Trajectory at K-th Collocation Point

- control_t solution_u_at(const int &k) const

Get Control Trajectory at Time Point ‘t’ (interpolated)

- control_t solution_u_at(const scalar_t& t) const

Get Optimal Parameters

- parameter_t solution_p() const

Get Dual Solution

- dual_var_t solution_dual() const